In previous posts in the TMLP series, I have described what an ML system/data developer should learn from turtles and tadpoles. This post describes what developers should learn from moray eels.

That’s a moray

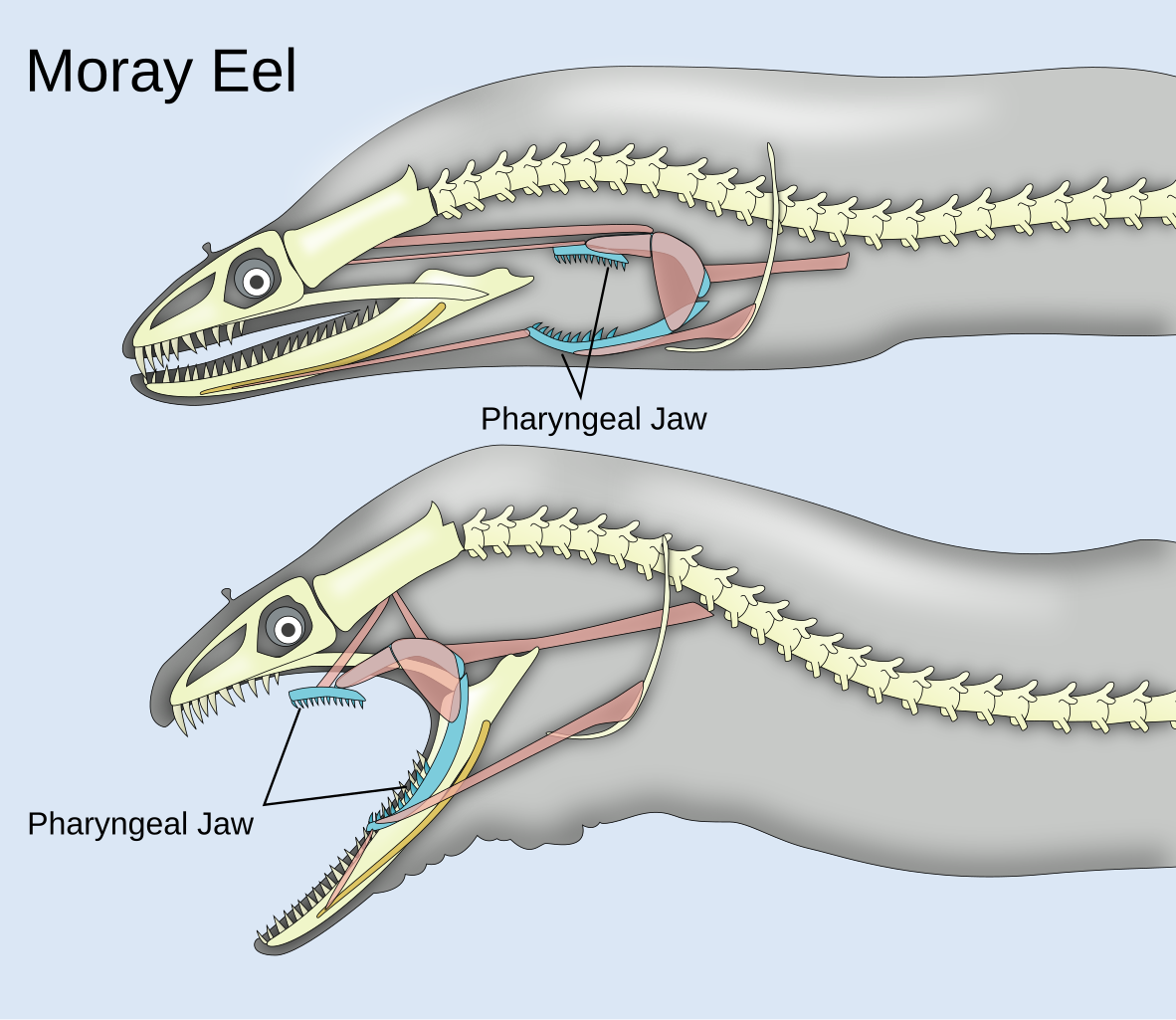

As an anonymous poet1 has said:

When an eel has a maw

with a pharyngeal jaw,

that’s a moray.

When the jaws open wide

and there’s more jaws inside,

that’s a moray.

As you feed the turtles in your ML system, you want to balance your data like a moray’s teeth: there are some teeth you see and some teeth you don’t. Morays also usually do a good job of hiding their long bodies in a hole or crevasse, just showing their head with a sarcastic toothy smile.

The data you know

There are many benefits that come from knowing your data in detail:

- Understanding complexity of the task: Through close inspection of individual examples as well as exploratory descriptive statistics, you can develop better intuitions about what factors matter, what cases count as important or negligible, and what the scope of the problem is

- Surprising failure modes: Data exploration will turn up problematic cases that you would not expect from just imagining the system, or that you might conflate with other cases without a deeper qualitative understanding. In a complete system, error analysis over a sample of usage can highlight the most important problems and identify what component in the system needs improvement.

- Divergence between datasets: Looking at data samples and exploratory analysis of datasets can reveal important differences between datasets, such as differences between training data and validation data, or differences between your curated test data and what you know about live usage data. These divergences could be different formatting, different pre-processing, or distribution shifts. Maybe somebody “cleaned up” your data in a way that left strange artifacts, or maybe the data hasn’t been cleaned up when you thought it was. Maybe one dataset is taking the whole system as the scope of its input and output, while another dataset was prepared for the scope of just one component, where the actual system would apply additional processing before the input or after the output.

The data you don’t

But the opposing force is that the more you directly use knowledge of the data to improve the system, the worse that data functions as an estimate of or proxy for the data in the next layer in your turtle stack. The more familiar framing of this principle is “don’t train on your test data”, but the hazard is more general.

You indeed do need to be careful not to copy examples from the test data into your training data, and avoid having the same random grouping variables (such as speakers in a speech dataset or queries in a question-answering dataset), if you want your system to generalize to new random groups.

You also need to watch out for data leaking across individual evaluation layers, such as doing detailed error analysis on all of your test data or setting your model training hyper-parameters based on your component/task test data. In the new prompted LLM paradigm, this could be using examples from your development data as few-shot examples in the prompt, or optimizing your prompt based on your test data.

Your goal is to build a system that generalizes over the data you know well, and beyond the data you are using to evaluate, to new data appearing in your live system. When you use information about your test data to fix things in the system, you are improving your system’s evaluation score but over-fitting, lessening the value of your test data, as it is now a worse estimate of live data. You’re making the test data less like the live data, because it is now special to the system, in that there are elements or aspects of the test data that are essentially known to the system.

How to keep your smile

This is in some sense unavoidable, because evaluation is essential to improving the system, and evaluation bleeds the novelty from the test data. But you can limit that effect while gaining value from evaluations by doing things like:

keeping the details of your best test data known only to the annotators, so that information is shared about the task scope and labeling guidelines, while the overall evaluation scores remind you to stay humble

keeping matched dev and test sets split from the same distribution, and only use the dev set for things like error analysis and hyper-parameter tuning, as the divergence in scores between the dev and test sets will indicate how much the dev data has been exhausted

do exploratory analysis of your dev and test sets together, to validate that they are indeed comparable and to understand how they differ from your other datasets, but when looking at particular examples, only look at dev data

split collected live data by time (e.g. monthly), and use the most recent few blocks to curate test data, while using older blocks for dev data, so that your fresh test data continues to approximate live data

when adding examples to a training set or an LLM prompt, only use collected/generated examples “inspired by” the examples from your error analysis, not examples that are the same or too similar

By using strategies like this, you can learn plenty from your evaluations while keeping reasonable expectations about your system as deployed.

Footnotes

If you know the origin, please let me know. I have not been able to trace its source beyond instagram copypasta circa 2000.↩︎